Stretching is supposed to make your hamstrings feel better—looser, lighter, more flexible.

So why are you experiencing only temporary relief at best—and often feel even more sore after stretching?

There’s a deep cultural belief in the power of stretching to reduce pain, improve mobility, and prevent injury. The support for those claims is, at best, inconsistent or non-existent. 1,2 If you’ve found this article, you’ve likely noticed a pattern yourself: every time you stretch your hamstrings, they get worse.

At Smith Performance Center, we see this pattern constantly. The sensation of “tight” hamstrings is rarely about flexibility—even in those with limited motion. We hear people complain of tightness in tissue disorders that actually cause more motion than normal.

More often, it’s a protective signal that something is off in how your system is moving, processing information, or managing load.

In this article, we’ll walk through what actually causes post-stretching soreness and why it’s time to stop pulling on your hamstrings—and start solving the real problem.

We’ll outline the causes and give you a test activity to determine your specific issue.

You Don’t Know What You’re Actually Stretching

That “hamstring stretch” may not be hitting the muscle at all.

The pull you feel could be coming from fascia, tendon, joint capsule, or even the nervous system. 3,4 You may also be feeding into a dysfunctional motor pattern—bypassing a limited joint, stretching something that’s already too mobile, and driving instability.

Or you might be misinterpreting a normal referral pattern from the back as a “good stretch that really gets it.”

And by “gets it,” what you’re really doing is irritating an injured structure.

The point is this: pain or tightness afterward means you’ve exceeded that structure’s tolerance, not improved it—whatever the structure actually is.

At Smith Performance Center, we call this a tissue response level—a way of defining when a structure consistently becomes symptomatic after load or tension.

There are six levels, but the purpose is simple: to create a clear feedback loop. A Level 2 tissue response means symptoms appear after the activity—in this case, after stretching.

If you consistently get symptoms after stretching, it’s not therapeutic; it’s provocative. Whatever structure you’re tensioning isn’t responding well to that input.

For a deeper dive into the different causes of hamstring tightness, read our related article: Why Your Hamstrings Always Feel Tight (and Why Stretching Isn’t Solving It)

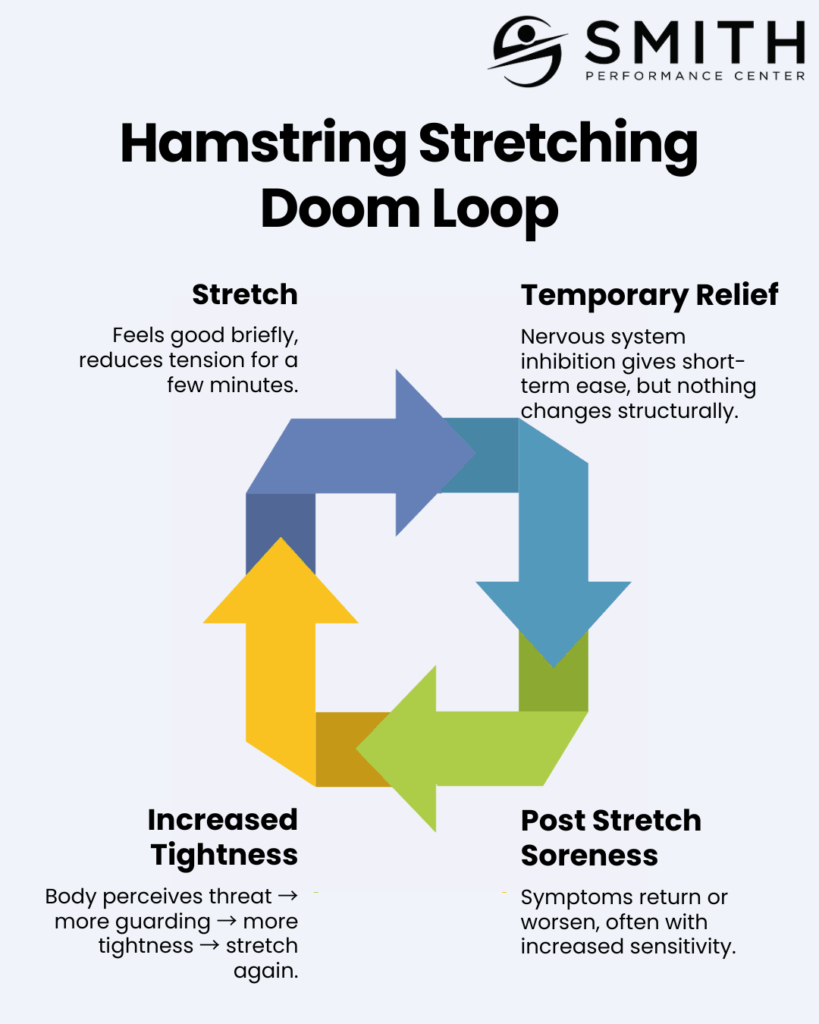

A more accurate view of that “tightness” or pain you’re trying to stretch away is that it’s a protective response from your body.

The momentary “release” you feel is short-term inhibition—your nervous system turning the alarm off for a few minutes. When that effect fades, the sensation returns, often stronger than before.

If every stretch follows the same pattern (stretch → relief → soreness → tightness → stretch again…) you’re not lengthening a muscle—you’re aggravating a sensitive structure.

Test #1 – Stop Stretching Your Hamstrings

If this sounds like you, the first rule of “tight hamstrings” is to stop stretching for a period of time. Most people notice a rapid reduction in soreness when they do.

You’re Stretching a Nerve, Not a Muscle

Let’s start with a quick anatomy review.

The hamstrings are three muscles—the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris. They all attach to the ischial tuberosity (your “sits” bone) and connect to the medial tibia, posterior knee, and fibular head, respectively.

The sciatic nerve runs directly next to the ischial tuberosity and then travels beneath the hamstring bellies into the back of the knee. This is why aggressive massage or pressure along the lateral ischial area, mid-posterior thigh, or behind the knee can easily irritate a very large, very important peripheral nerve.

Most people don’t realize that the classic hamstring stretches—sit-and-reach, toe touch, or seated hamstring stretch—double as neural-tension tests.

Two tests are commonly used in clinic: the straight-leg raise and the slump test. When you “wind up” the nervous system by flexing the foot and the head, your available range decreases because of the nerve, not the muscle. Even though the sciatic nerve can move a few millimetres relative to surrounding tissue, the hamstring can lengthen much more. 3,5

At Smith Performance Center, we differentiate between muscle tightness and nerve tension by testing how the nervous system behaves under load. The simplest way to check this yourself is to tension the nerve and then see if symptoms change when the nerve is unloaded.

Test #2: The Nerve Tension Check – Self Slump Test

- Sit tall on a chair or bench.

- Flex your foot toward your shin (dorsiflexion).

- Bring your chin toward your chest (neck flexion).

- Slowly extend your knee.

If this position increases your tightness or reproduces your familiar symptoms, you’re not stretching a muscle—you’re stretching a nerve.

What you should be doing instead is neural flossing, not stretching. Nerves heal and adapt through gliding—movement that allows them to slide relative to surrounding tissues—not through tensile load.

When you pull on a sensitized nerve, which means mechanically sensitive, you’re not improving flexibility—you’re re-irritating the system.

The Low Back Commonly Refers to the Hamstrings

Your hamstrings can feel tight even when the problem starts higher up.

This requires another review of the anatomy.

Your lumbar spine has 5 vertebrae with discs – specialized ligaments that absorb and transmit force- with nerve roots that exit at each level via the vertebral foramen. The front of the vertebrae is the body and in the back, there are two facets that link up with the facets above and below.

All of the structures, even ones I did not hit, can cause pain or the sensation of tightness. Sometimes this presents where the structure is, but often, it will refer to the back of the legs – right where you are perceiving hamstring tightness with or without low back pain. 6–9

We often suspect the low back as the driver of hamstring tightness when:

- There’s coinciding or recent low back pain.

- Tightness began after a back irritation.

- Symptoms increase with activities that load the spine, like sitting for long periods or driving.

Just like in the case with a nerve, the classic hamstring stretches also load the back. This means that the stretch you think you are doing is not stretching the hamstring, but provoking the back leading to a referral pattern that makes you feel more sore and more tight.

Test #3 – Active Range of Motion of the Low Back

- Stand tall and perform:

- Forward flexion

- Extension

- Side bending to the right and left

- Pay attention to symptoms during and after the movement.

If these motions cause pain or lead to a delayed increase in hamstring tightness, your symptoms are likely referred from the low back.

A simple way to confirm this is to perform gentle lumbar traction using a band or suspension system for 3–5 minutes.

If the traction reduces your feeling of tightness and improves range of motion, the back is the most likely source.

The Hamstrings Aren’t Tight — They’re Over-Activated and Mispatterned

If we rule out the nerve and low-back causes of hamstring tightness, what happens when you stretch the muscle itself?

One pattern we see often at Smith Performance Center is that the hamstrings are actually firing during the stretch.

The cause of this can be complex and requires careful assessment to uncover.

Let’s review the basics of how a muscle fires.

Every muscle is controlled by a motor neuron connecting the central nervous system. An electrical impulse travels along that neuron, generating an action potential that must reach a certain threshold to make the muscle contract.

That threshold isn’t fixed—it changes depending on your nervous system’s state – peripheral and central, the interaction between different muscles when producing an action, and the level of fatigue. When your threshold drops too low, the muscle fires too easily, leading to cramping, guarding, or a constant feeling of tightness.

Think about what you instinctively do when a muscle cramps: you stretch it. That stretch triggers the Golgi tendon organs, which briefly inhibit the muscle’s activity.

It feels better—but that “release” is temporary.

The temporary fix often gets people addicted to the relief but it is not permanent.

A faulty movement pattern and lowered threshold aren’t corrected by temporarily shutting down a muscle.

It’s corrected by addressing why the threshold is lowered and retraining when and how much the muscle fires.

Most “tight” hamstrings are over-working because other muscles aren’t doing their job—or because the system is stuck in a co-contraction pattern.

We call this an altered neuromuscular state.

Research supports this mechanism: Schwellnus and colleagues demonstrated that muscle cramping and over-activation occur when spinal reflex control shifts toward excitation—increased muscle spindle activity and reduced Golgi tendon inhibition—creating exactly the altered neuromuscular state seen in chronically “tight” hamstrings. 10,11

When glute control12 or pelvic stability falters, a lowered firing threshold in the hamstrings combined with an dysfunctional pattern result is a muscle that feels tight, sore, and unwilling to lengthen—because it’s a pattern built over time, not short and needing to be lengthened.

Test #4 — Hamstring Cramping and Poor Patterning

- Lie on your back and perform 10 controlled glute bridges.

- Focus on driving through your heels and using your glutes.

- Then stand up and try to touch your toes.

If you feel more tightness after the bridges—or if your hamstrings cramp during the movement—you’re likely dealing with a patterning problem with a lowered hamstring firing threshold.

And the soreness is coming from you forcefully pushing through a contracting muscle.

Your hamstrings are firing when they shouldn’t be, and in this situation, compensating for poor glute activation due to hamstring dominance.

Remember this is just one pattern and can happen in many different ways.

The solution isn’t more stretching—it’s retraining coordination.

Re-establishing glute control and timing restores balance to the system. We used an exercise called the modified glute bridge with a foam roller to target just the glute and reintegrate into patterns that feel tight.

The Hamstring Itself Is the Source of Soreness

We’ve ruled out the nerves.

We’ve ruled out the low back.

We’ve even cleared patterning issues and the problem of the hamstring firing too easily.

Sometimes, it really is the hamstring.

The hamstring can develop problems due to:

- True muscle weakness – a genuine loss of contractile strength, not just inhibition.

- Proximal or distal tendon injury.

- Muscle strain or partial tear.

- Myofascial trigger points.

When the hamstring muscle is injured, tightness is a common complaint, stretching is a common irritant, and post-stretching soreness is the natural response.

Each part of the hamstring—muscle belly, proximal tendon, or distal insertion—can generate pain.

Test #5 — Resistive Testing of the Hamstring (The “Shoe-Off Test”)

This test is a simple and reliable way to load the hamstring:

- Sit on the edge of a chair with your foot flat on the ground.

- Try to pull your heel back as if you’re trying to take your shoe off, while keeping your foot planted.

- If this causes pain or reproduces your soreness, the hamstring itself is likely the source of your symptoms.

When this test is positive, stretching is not providing a therapeutic effect—it’s provocative.

Instead, the goal is to create what we call a therapeutic gap:

- Remove triggers that irritate the hamstring.

- Add treatments and exercises that improve tissue tolerance and promote healing.

As tissue capacity improves, the hamstring becomes more resilient. When that happens, stretching is once again tolerated—not because it healed the muscle, but because the muscle healed enough to tolerate stretch.

The Bottom Line

Once you identify which of these five causes applies to you, the path forward becomes clear—and it rarely involves more stretching, especially if that stretch produces soreness from a delayed feedback loop.

Hamstring soreness after stretching isn’t a sign of progress; it’s feedback that the system you’re pulling on isn’t ready for more tension.

Whether the cause is neural, spinal, pattern-driven, or a true tendon injury, each requires a specific strategy—and none of them start with “stretch harder.”

If you’ve been battling “tight” hamstrings that never seem to improve, it’s time to determine which of these six reasons fits you.

Book an initial evaluation at Smith Performance Center—we’ll help you find the real source of your hamstring pain and build a plan that actually works.

References

1. Nuzzo, J. L. The Case for Retiring Flexibility as a Major Component of Physical Fitness. Sports Med. 50, 853–870 (2020).

2. Weppler, C. H. & Magnusson, S. P. Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation? Phys. Ther. 90, 438–449 (2010).

3. McHugh, M., Johnson, C. D. & Morrison, R. H. The role of neural tension in hamstring flexibility. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 22, 164–9 (2010).

4. Kuilart, K., Woollam, M., Barling, E. & Lucas, N. The active knee extension test and Slump test in subjects with perceived hamstring tightness. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. – INT J OSTEOPATH MED 8, 89–97 (2005).

5. Topp, K. S. & Boyd, B. S. Structure and Biomechanics of Peripheral Nerves: Nerve Responses to Physical Stresses and Implications for Physical Therapist Practice. Phys. Ther. 86, 92–109 (2006).

6. Lorio, M. P. et al. Defining the Patient with Lumbar Discogenic Pain: Real-World Implications for Diagnosis and Effective Clinical Management. J. Pers. Med. 13, 821 (2023).

7. Bogduk, N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. PAIN 147, 17–19 (2009).

8. Marks, R. Distribution of pain provoked from lumbar facet joints and related structures during diagnostic spinal infiltration. Pain 39, 37–40 (1989).

9. Ohnmeiss, D. D., Vanharanta, H. & Ekholm, J. Relation between Pain Location and Disc Pathology: A Study of Pain Drawings and CT/Discography. Clin. J. Pain 15, 210 (1999).

10. Schwellnus, M. P. Cause of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps (EAMC) — altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? Br. J. Sports Med. 43, 401–408 (2009).

11. Schwellnus, M. P., Derman, E. W. & Noakes, T. D. Aetiology of skeletal muscle ‘cramps’ during exercise: a novel hypothesis. J. Sports Sci. 15, 277–285 (1997).

12. Wagner, T. Strengthening and Neuromuscular Reeducation of the Gluteus Maximus in a Triathlete With Exercise-Associated Cramping of the Hamstrings. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2010.3110 (2009) doi:10.2519/jospt.2010.3110.