The Evolution of Thought Around Meniscus Injuries

Clinical practice is filled with successes and failures. For some reason, failures tend to linger in memory the longest and often drive the biggest changes in how we approach patient care. A significant moment in my clinical career involved a meniscus tear, knee pain, and the need for surgery.

‘Clinic practice is filled with successes and failures. Any failure should drive improvement in the system.’

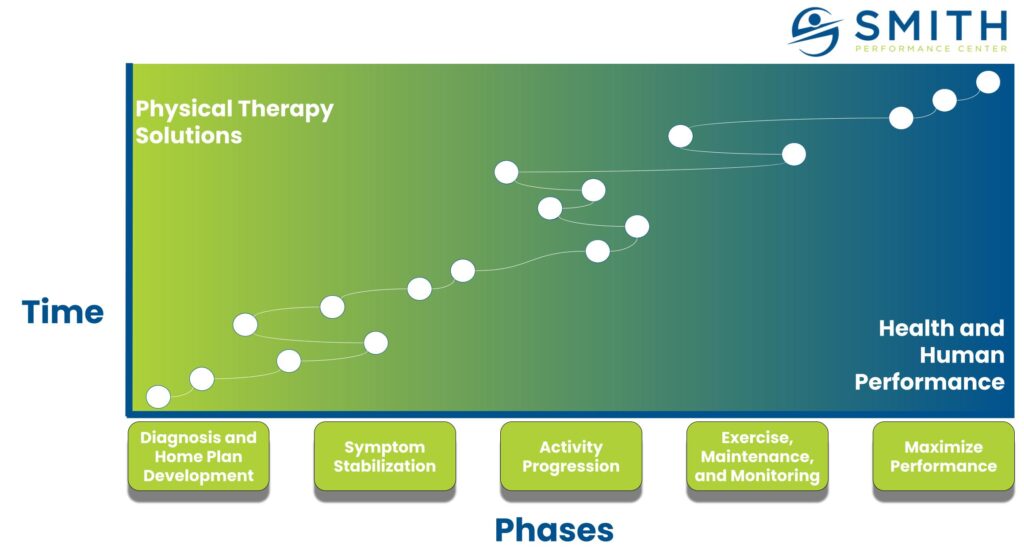

One of the most impactful shifts in my approach to knee pain, particularly in cases involving meniscus tears, came from a repeated clinical pattern: patients improving, then regressing, over and over. This frustrating cycle forced me to rethink my process and align it with a more structured framework—one that incorporates the Smith Performance Center Phases.

This helped me answer the question, “Does a meniscus tear require surgery, or can it be successfully rehabbed without going under the knife?”

The Traditional View: Meniscus Surgery vs. Rehab

For years, meniscus tears were considered a primary cause of knee pain, often leading to partial meniscectomies. When patients presented with pain and catching sensations, the meniscus was assumed to be the culprit. This mindset led many to believe that removing or trimming the meniscus would resolve their symptoms. However, research has repeatedly shown that partial meniscectomy is often no more effective than sham surgery.

A Case of Repeated Knee Pain – The Shift in Approach

Round 1: A Limited Understanding

I once worked with a patient experiencing sharp knee pain with occasional catching. She had mild joint effusion and full knee motion but reported pain at end-range extension. The patellar tendon was tender, and she walked with a gait abnormality where the knee was not fully extending at initial contact and then failed to flex during loading response, preventing proper force absorption through the quadriceps.

At the time, I focused on treating what I thought was the main issue: patellar tendinopathy. My approach relied heavily on quad and glute exercises, ignoring the larger biomechanical picture. I noticed a loss of knee extension, but my emphasis on muscle, not on other possible limits of the motion, led me to ignore it. As a new therapist, I assumed the right diagnosis and moved too quickly in targeting the muscle strength deficits. I missed that there were multiple pain generators and never stabilized her symptoms. The result? A frustrating cycle of improvement followed by regression. Eventually, the patient opted for surgery, believing the meniscus tear was the root of her pain.

After surgery, she improved—at least temporarily. But this wasn’t the end of the story.

Round 2: A New Perspective

A few years later, her knee pain returned, and it was worse than before. She was doing less, and normal walking had become increasingly symptomatic. Imaging showed further meniscus degeneration, and she once again considered surgery. But this time, my approach had changed.

Instead of fixating on tendinopathy, I focused on the problem – what is causing the pain and how can I verify I had them all. Meniscus mobilizations and knee extension work helped achieve pain-free extension and proper quad activation, making walking pain-free. Addressing gait abnormalities was also critical—excessive knee extension at midstance had become a habit. To correct this, we used a heel lift to improve initial contact, setting up proper loading response. This adjustment completely resolved walking-related knee pain.

Consistent feedback and symptom retesting were essential. Using objective markers such as effusion levels and end-range pain, we ensured our interventions were working. However, day-to-day interaction with unmanaged triggers significantly contributed to symptom fluctuation, making normal walking more symptomatic. Identifying and addressing these hidden triggers was crucial in achieving lasting improvement.

But the big change was that I made no assumptions and focused on the right problem at the right time. It was the structured approach that made the difference. The result?

Complete symptom resolution—without surgery.

Integrating the Smith Performance Center Phases in Meniscus Rehab

One of the key takeaways from this experience was the necessity of a structured process in managing knee pain. This aligns with the SPC Phases:

Phase 1: Diagnostics and Home Plan Development

The key problem is determining whether the meniscus is the lone pain generator, one among many, or even just the symptom of a larger biomechanical issue. In her case, the primary contributors were the joint itself, the patellar tendon, and the anterior horn of the meniscus. All three had to be identified and addressed for effective treatment because addressing one often led to another becoming more painful.

Objective tests include assessing joint effusion presence, quad atrophy and weakness, and glute inhibition. Painful passive end-range extension often improves with terminal knee extension and menisco-tibial mobilizations. It is critical to see improvement in pain at a minimum, and long-term, we need full extension. Our team at SPC will rapidly retest treatment strategies ranging from tissue-specific treatments and artificial stabilization to neuromuscular and movement retraining. The home plan focuses on reducing irritation and improving joint movement early on to regain extension because it is the linchpin for normal movement with walking.

Phase 2: Symptom Stabilization

The key goal is empowering the patient to apply treatment to improve tissue capacity while reducing irritation to the injured structures. The approach includes pain-free joint mobilizations, quad activation without aggravation, gait pattern adjustments, and consistent retesting to ensure progress (what we call ‘key signs’—objective indicators such as improved knee extension, reduced swelling, and better quad activation, which help track progress.).

We find over and over again how critical it is for the patient to master the triggers and can make themselves feel better. Never let a good flare-up go to waste—it’s an opportunity to build confidence by managing pain independently, without always relying on a medical professional.

Owning the home plan and managing flare-ups reduces swelling, improves quad activation, and prevents the need for surgery.

Phase 3: Activity Progression

The key goal is building tissue capacity.

Walking, while not hard to do, involves significant load. Activity creep is normal, meaning you gradually do more and more. The difference between 2000 steps and 4000 may seem small, but that is a doubling of volume, not to mention an increase in gait speed that occurs as you feel better.

As your knee handles more load, recognizing subtle changes—like slight loss of extension before pain—helps prevent setbacks. Alongside monitoring changes in movement, progressive strength training is introduced to reinforce joint stability and load tolerance. Additionally, we focus on reducing contributing factors like glute weakness or inhibition, quad atrophy, and gait abnormalities that may limit tissue capacity (the clamshell can be a useful tool for overcoming a inhibition response, which is very common).

Phase 4: Exercise, Maintenance, and Monitoring

The key goal is long-term sustainability. Imaging will not show that your meniscus tear is gone. It will still be there but the pain and dysfunction is gone.

Ensuring proper mechanics are maintained during daily and athletic activities and periodic check-ins for early intervention if symptoms return is essential. To provide ongoing support and prevent setbacks, we implemented Open Clinics. These are quick check-ins where patients can receive assessments, adjustments to their treatment plan, and guidance on managing symptoms before they escalate. Open Clinics at Smith Performance Center were developed to ensure individuals continue training without being derailed by pain or injury. These 15-minute sessions help determine if an activity needs to be paused, if a program needs modifications, if a full medical evaluation is required, or if a home plan should be implemented to manage symptoms independently. Once you have a recurrent injury like this, you will always be at greater risk for it to return. We want to stay as active as possible and address any returns quickly and efficiently while improving your movements and fitness.

You will not be in an active rehab plan of care, but you need to notice the changes that indicate help is needed. Your home plan will still be a tool you want to return to if you start to notice negative changes.

Phase 5: Maximize Performance

In Phase 5, individuals are ready to push their limits, which naturally increases the risk of setbacks. However, with a well-structured plan that incorporates recovery and supportive exercises, they can continue progressing safely and effectively. Phase 5 bridges the gap between rehab, an active exercise habit, and peak, specific performance.

For those aiming to return to high-level activity with a specific goal, this phase ensures progress while managing the risks of pushing limits. Our coaches play a key role in monitoring progress and identifying early signs of poor knee tolerance to exercise. By making necessary adjustments in intensity, volume, or movement patterns, they help ensure continued progress without setbacks. Both in-season and off-season training must proactively account for your injury history. With planned adjustments, we ensure you maintain performance while minimizing the risk of flare-ups or setbacks.

The key goal is the focus on a specific challenge beyond pain resolution and staying active. This includes high-level loading strategies, sport or activity-specific drills, and ensuring tissue resilience to prevent future issues while managing fitness and fatigue.

Bridging the Phases to Research: Meniscus Tear Recovery

The transition from structured rehabilitation to research-backed decision-making is critical. By following the SPC Phases, patients can understand their progress, reduce pain, and improve function without relying solely on surgical intervention. Research supports this approach, highlighting the importance of conservative treatment before considering invasive options.

Meniscus Tear Recovery: What the Research Says About Surgery vs. Rehab

The groundbreaking 2013 study by Sihvonen et al. challenged the necessity of partial meniscectomy. Their study found no difference between patients who underwent actual meniscus surgery and those who received sham surgery. The conclusion was clear:

“Results argue against the current practice of performing arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in patients with a degenerative meniscal tear.”

This research, combined with my clinical experience, reinforces the need to move beyond a simple “tear equals pain” mindset. Instead, we must focus on diagnosing the actual pain source, stabilizing symptoms, and restoring function.

The Takeaway: A Smarter Approach to Meniscus Tear Rehab

If you have knee pain and a meniscus tear, surgery is not always the answer. It’s easy to get stuck at any phase—but each stage requires a different approach to move forward successfully.

Clarity in diagnosis, treatment, and recovery is the key to long-term success.

A structured, phase-based rehab approach can often achieve better outcomes—without the risks of surgery. By focusing on the right diagnosis, stabilizing symptoms, and rebuilding movement, you can break the cycle of recurring pain and return to an active, pain-free life—without unnecessary surgery.

Ready to take control of your recovery? Schedule a physical therapy evaluation or Movement Assessment at Smith Performance Center today!