In a session, the first rule as a practitioner is to make sure we do not lie to ourselves about what’s happening, and lying to ourselves is the easiest thing to do.

We can lie to ourselves when we make errors in reasoning due to a plethora of cognitive pitfalls like confirmation or optimism bias, overconfidence, or mistaken availability heuristics. This can ruin the chances of a great outcome if I only search for facts that confirm my dominant theory, or if I want the patient to have a great response so I ignore portions of the medical history that would lead me to a think of worse prognosis. These cognitive errors ‘help’ me to lie to myself.

One solution is to get very clear on what the patient is reporting.

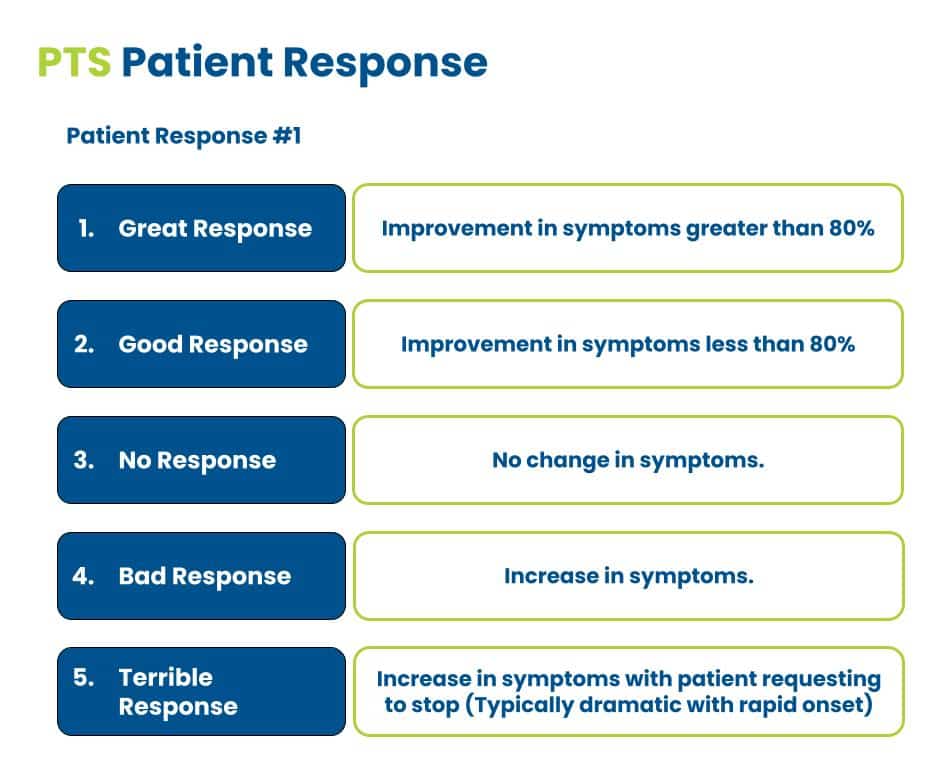

There are only 5 patient responses in the session: great, good, bad, terrible, and no response.

Certain pathologies readily respond to treatment. Think of medial heel pain involving a single structure like the abductor hallucis or the flexor digitorum brevis. But there are people who come in with multiple pain generators with each being sensitized in different ways. Even if I were to help one, it may only reduce the pain by 10 to 20 percent. There can also be interactions where a treatment that helps one pain generator, triggers another, masking progress.

This is where the patient response strategy becomes critical.

The patient response

So in an effort not to lie to myself and to get clear thinking, I only categorize a great response as greater than 80%. This is a cutoff that you see in literature for injections amongst others. It reduces the likelihood that the patient’s response is purely placebo while increasing my confidence in my current hypothesis.

If it is positive but not 80%, then it’s a good response.

If there is no change no matter what I do, then I categorize it as no response.

If they feel a worsening of symptoms, that is considered a bad response.

A terrible response is when the patient gets dramatically worse, nothing helps, and we can no longer apply the treatment.

What the response means

Each response provides feedback on my main hypotheses: diagnosis, treatment decision, and plan of care.

One of my central clinical beliefs is that nothing is proven. I try to disprove every hypothesis through multi-level testing. Uncertainty is the rule, by which I mean that there are limitations to my prediction of what will happen. Uncertainty impacts every level of the session from the direct care of the patient to management to the basic science of pathology.

I don’t care what any other practitioner has found or told the client.

I don’t care if there is imaging that shows a disc herniation or ultrasound findings for a tear or if diagnostics injections resolved the pain previously.

I will use that information but still create my own educated guesses and then test them. I consider this pragmatic method more effective and versatile. The in-session responses are feedback on my in-session experiments. I have tried to train myself to view a great response just as more support for my hypothesis. The same thing with terrible responses.

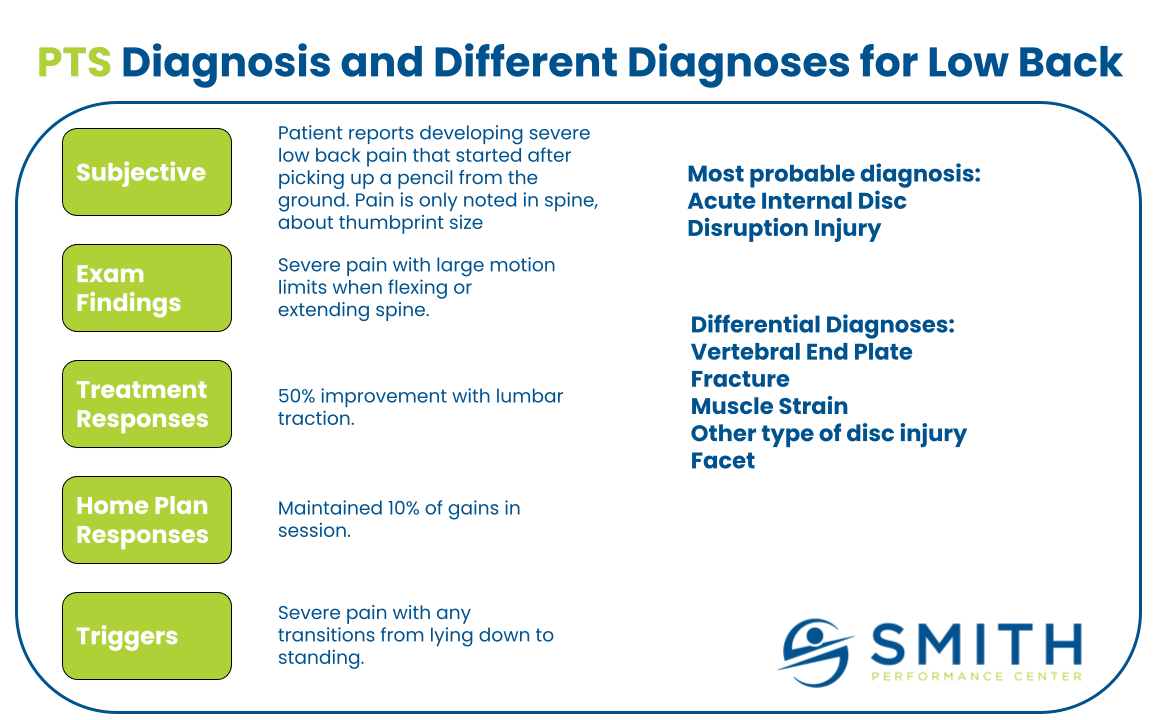

Imagine a patient coming in with new, severe low back pain.

They can’t stand straight, sitting is agony, and the morning pain is unbearable. When I ask about numbness or tingling, they say no, there is just nasty pain in their back about the size of a palm print. My diagnostic hypothesis is that they have a lumbar disc injury without involving a nerve root. My treatment strategy is considering two factors: what will reduce the pain right now and what will confirm my diagnostic hypothesis. I decide to provide side-lying lumbar traction.

After 5 minutes, I ask how they are feeling and then tell me one of the following:

- Great response – ‘the pain is gone!’

- Good response – ‘the pain is less but I still feel it if I move.’

- No response – ‘the pain is the same. Nothing you are doing is helping.’

- Bad response – ‘the ache is getting worse. I feel down into my butt now.’

- Terrible response (typically we do not make it to 5 minutes) – ‘Please stop! That is really hurting and making it worse. I hate you.’

I have had every one of these responses to treatment, except the ‘I hate you’ is not said out loud. Even when the setup is the same, each response is possible. Here is the first decision tree from the patient response that calls for strategy and a pragmatic approach.

Decision based on the first patient response

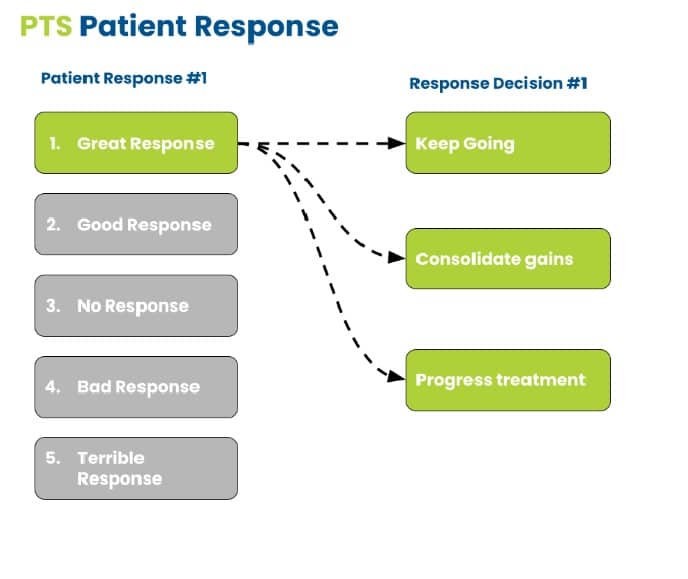

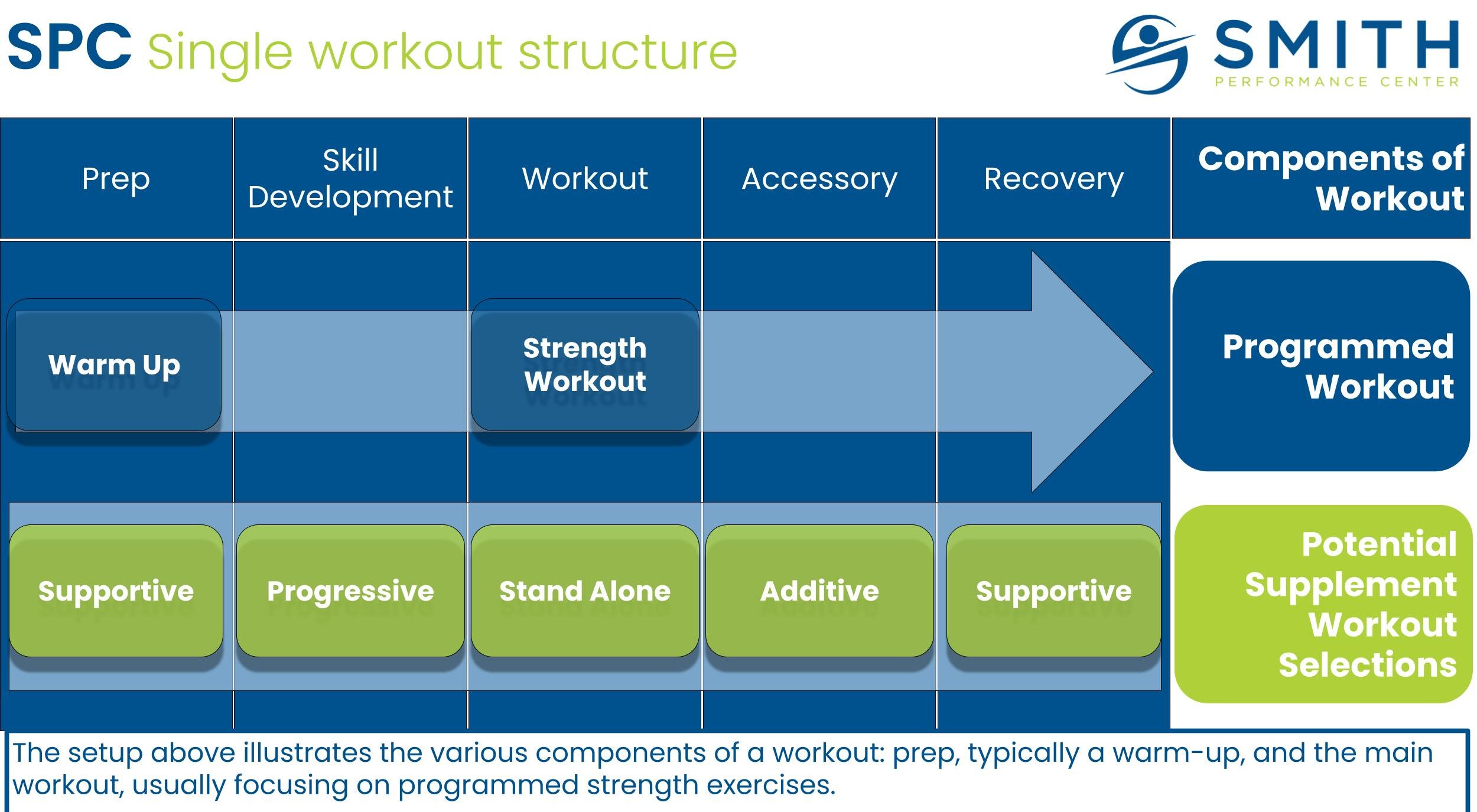

The clinician’s decision based on the in-session response allows for an infinite number of actions.

Complexity often trips up clinicians if they miss the strategic implications and label their decision too specifically. There is also an issue with siloing, which means only one type of treatment is considered. This is better explained with a graphic.

As you can see above, we had a great response. The idea is to disprove my hypothesis. The fact that there was improvement supports my hypothesis and makes the probability much greater that my idea is correct.

We want to constrain the decisions at this point.

There are 3 for me: keep going with the same treatment, consolidate the gains, and move to home plan development or progress to more advanced treatment.

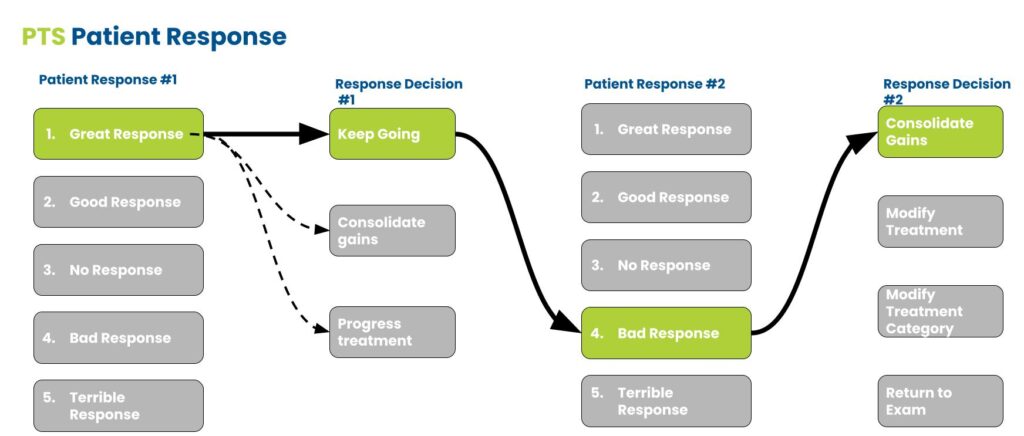

I decide to keep going and after 5 minutes I reach another decision based on the patient’s response.

AND crap. I got greedy and now the patient hurts more but is still quite a bit better than when they came in. It’s like sitting at the blackjack table. I am ahead of where I started when I sat down. Do I keep going till I lose all of my money or risk it and try to make more?

Even though I had a bad response, it’s still great information.

This is critical to note because any response is useful with a good strategy.

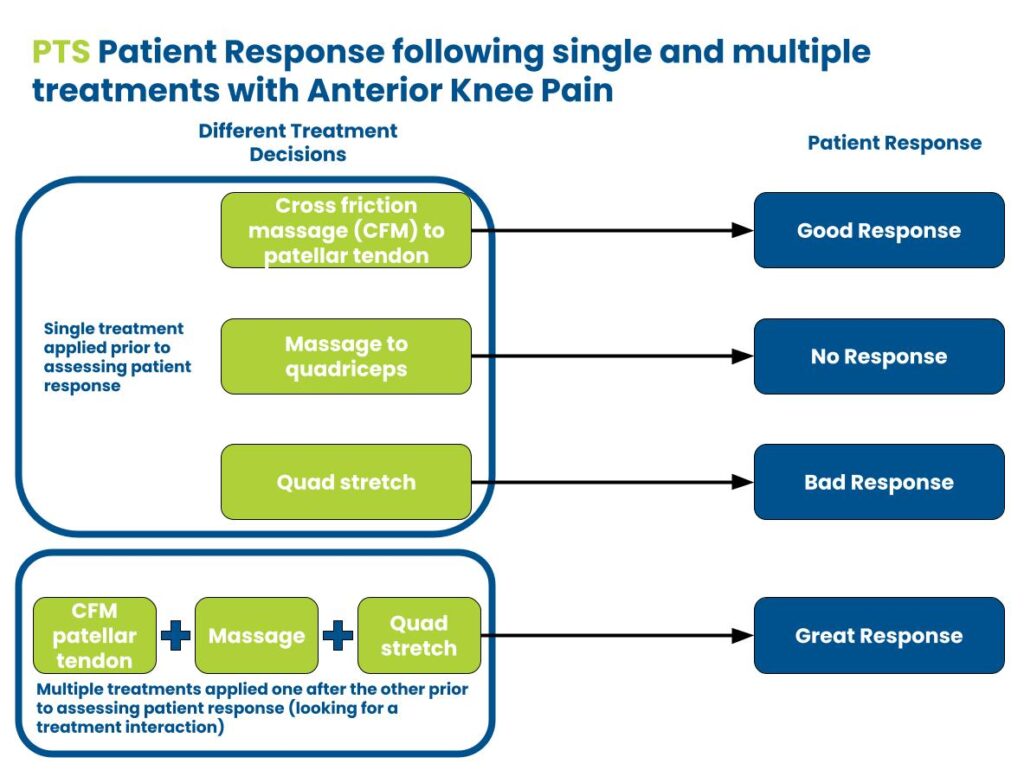

Now, I know the patient has treatment tolerance limitations. I could modify the treatment by making it more gentle or build a better home plan that uses a timing schedule (This is why doing all of your home exercises at once can actually backfire for some patient presentations). I can try a different treatment category or start to think of treatment combinations that interact with each other to improve the overall response. For example, a patient with anterior knee pain will often report a great response with coupled treatments while the singular treatment application is less.

In-session patient response strategy

Once again, the point is that there are endless possibilities.

The issue is to ignore the strategic implications. If you idiotically apply the same treatment over and over with the exact same response without considering how this supports or does not support your original hypothesis, you have no strategy. A physical therapist can get lucky with this single-minded treatment plan, but will also fail every single case that does not fit this non-strategic, inflexible approach. This is where we see people that come in after years of treatment because they have been told there is scar tissue all over their body and the only solution is to apply active release technique or dry needling or massage or manipulation or exercise or stretching or yoga.

A strategic approach while monitoring the patient response will result in the best outcome.