Why Do We Focus on Long-Term Development in Strength Training?

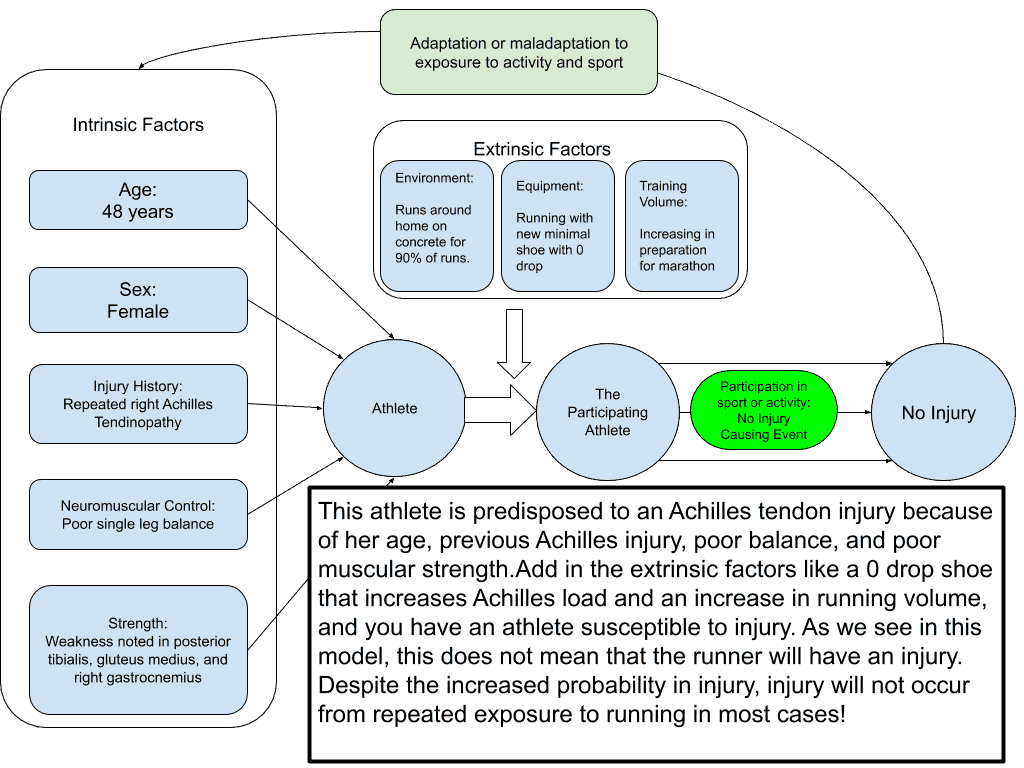

Activity brings benefits and risks. Every step, competition, or practice is an exposure that impacts the body. The questions – how do I get better and how do I stay healthy – are part of a dynamic and constantly changing system (Figure 1). We can model that system to show how the activity, like running or playing football, impacts your next exposure.

The Basics

If you are a runner, you need to run.

If you want to get stronger, you need to lift.

If you want to be a great triathlete, you need to swim, bike, and run.

If you want to shoot well during a basketball game, you have to shoot over and over.

You get the picture (maybe). There are no prodigies (Ericsson 2004). Reaching your potential requires effort and time. However the very activity you participate in impacts the next time you do it. This process is endless until you stop being active or competing in sports.

Dynamic Recursive Model of Long-Term Development: What does this model mean?

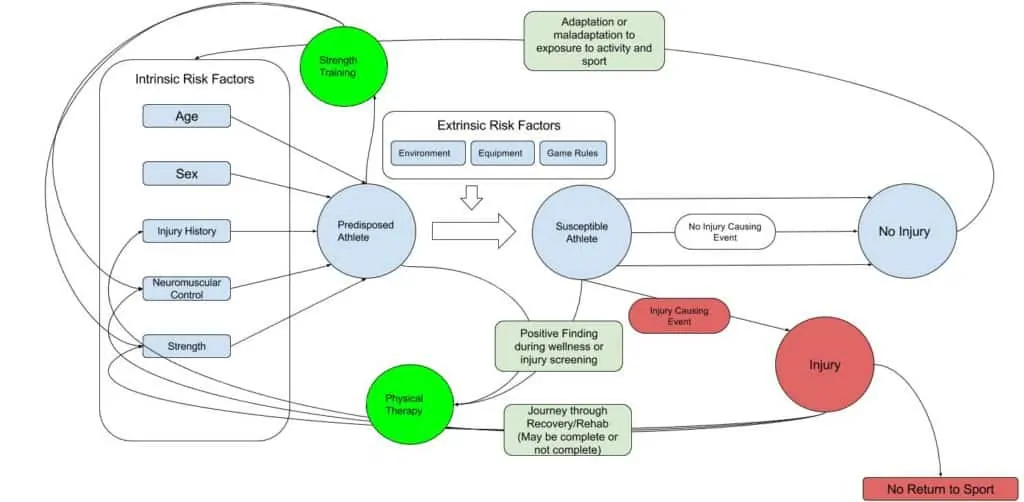

We get one body when we start our life’s journey. There are things like sex, age, injuries, and how you move that impact your performance along with your risk for having an injury. These are intrinsic factors (Figure 2).

Some can be changed, like your strength while your injury history is what it is. From these factors, we can build and analyze our Athlete profile. Previous ACL tear increases your risk for a subsequent ACL tear. Ankle sprains increase the likelihood you will have another ankle sprain and a more serious knee injury.

Next, we look at the sport or activity. Using football, we can look at the playing surface (turf or natural grass), which changes the risk of an ACL tear. For Volleyball, we can look at how many jumps are required to participate (more exposure to a high-risk movement). These are extrinsic factors, meaning they are external to the person. As you can see from Figure 3, the extrinsic factors impact the athlete during every exposure and can include equipment, game rules, training volume, competition or training, game surface, and shoe wear.

The participating athlete has decided to do an activity. The activity can be anything from running to jumping to a walking program. It can be organized with formal rules, or a random game of tag. The intrinsic factors and extrinsic factors slam together in the participating athlete during the exposure to the activity.

The exposure is critical if the activity is important. You only get better by doing something over and over and over (purposeful or deliberate practice – the topic of another post). You only get significant adaptation from exposures so we want to get as many as possible.

So far, this has been a pretty abstract review. Let’s look at an example to make it more clear.

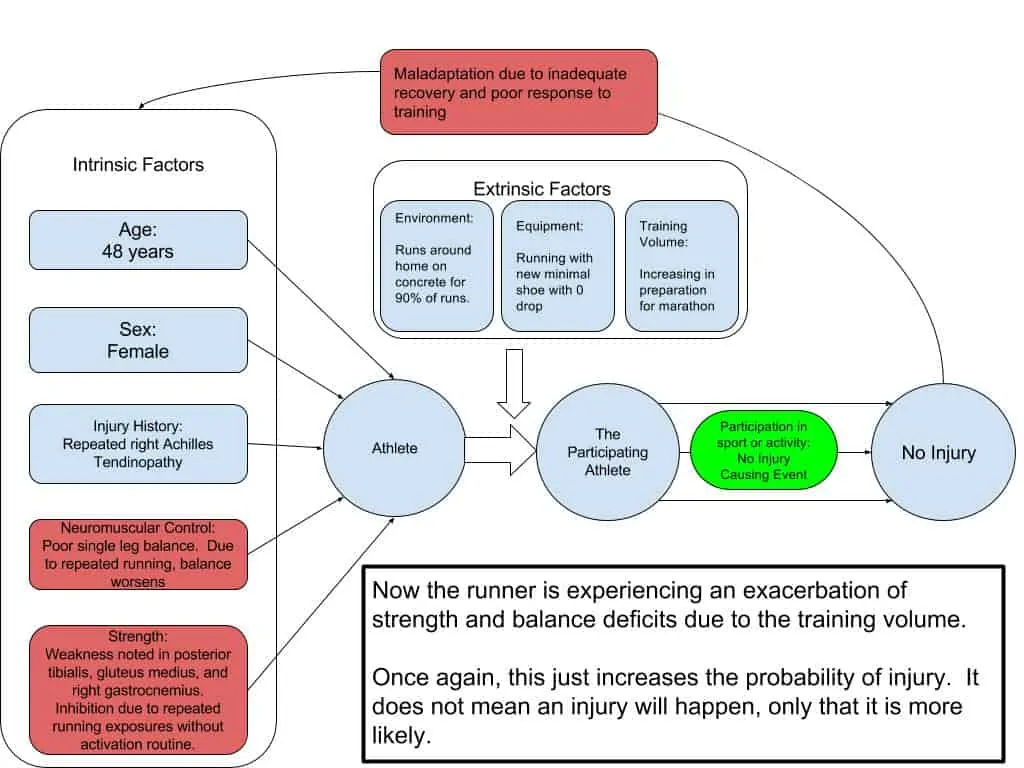

Dynamic Reclusive Model of Runner

So here we see an athlete that is at high risk for an Achilles injury (Figure 3). This does not guarantee injury. It just means that the probability of injury is greater when compared to someone younger, no history of Achilles injury, normal balance, and normal strength. Further, shoe selection and training plans are creating an even greater probability of injury. The majority of runs for this runner will result in no injury, BUT every run will result in some response in the body. The body’s adaptation will augment the intrinsic factors. For example, running longer distances can negatively impact balance and strength (Figure 4). A series of runs without adequate recovery and nutrition can cause the strength and balance deficit to drop off a cliff. We call this maladaptation.

What does this look like?

This is where the potential for strength training, injury screening, and physical therapy are seen. We can positively impact the intrinsic factors, extrinsic factors and the exposure to make sure the runner’s probability of injury is as low as possible (see Figure 5).

Her running gait shows poor control during the stance phase with excessive knee valgus and pelvic drop along excessive dorsiflexion at midstance. The excess dorsiflexion will increase the load on the Achilles tendon.

Cuing to increase step rate normalized the dorsiflexion at midstance.

Strength training during her build-up toward a marathon will focus on modifiable intrinsic factors, so a balance and strengthening program is implemented.

The beauty of the dynamic recursive model is that it responds to the exposures of physical activity. It does not assume that a person will always have the same risk profile. It also does not assume that risk for injury means you will get injured. There are built-in screenings and assessments that are constantly rebuilding the intrinsic and extrinsic factors allowing the maximum training potential (i.e. the most exposures to the activity like running) while minimizing the risk for injury.

Reaching your potential is not easy. Most people understand that to get better, you need to do the activity. It is less clear to me that people understand that injury risk requires as much thought as the training plan for running faster or getting stronger.

References

Meeuwisse, W. H., Tyreman, H., Hagel, B. & Emery, C. A Dynamic Model of Etiology in Sport Injury: The Recursive Nature of Risk and Causation: Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 17, 215–219 (2007).

Ericsson, K. A. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic medicine 79, S70–S81 (2004).